A recent study suggests that ancient hunter-gatherer communities in Europe actively avoided inbreeding. The research, published in the journal PNAS, focuses on the genomic analysis of skeletal remains from several burial sites in France, including Téviec, Hoedic, and Champigny.

Led by researchers from Uppsala University in Sweden, the study examines the genomes of 10 individuals who lived between 8,300 and 6,760 years ago.

These individuals belonged to some of the last hunter-gatherer groups in Europe, existing alongside newly arrived Neolithic farming communities.

Contrary to previous assumptions, the study reveals that blood relations and kinship were not the sole determining factors in the composition of these communities.

Despite their small population sizes, the hunter-gatherer groups displayed a remarkable lack of biological relatedness among individuals. This suggests that they had developed sophisticated cultural strategies to avoid inbreeding.

“We know that there were distinct social units — with different dietary habits — and a pattern of groups emerges that was probably part of a strategy to avoid inbreeding,” explains Luciana G. Simões, the lead researcher and a geneticist at Uppsala University.

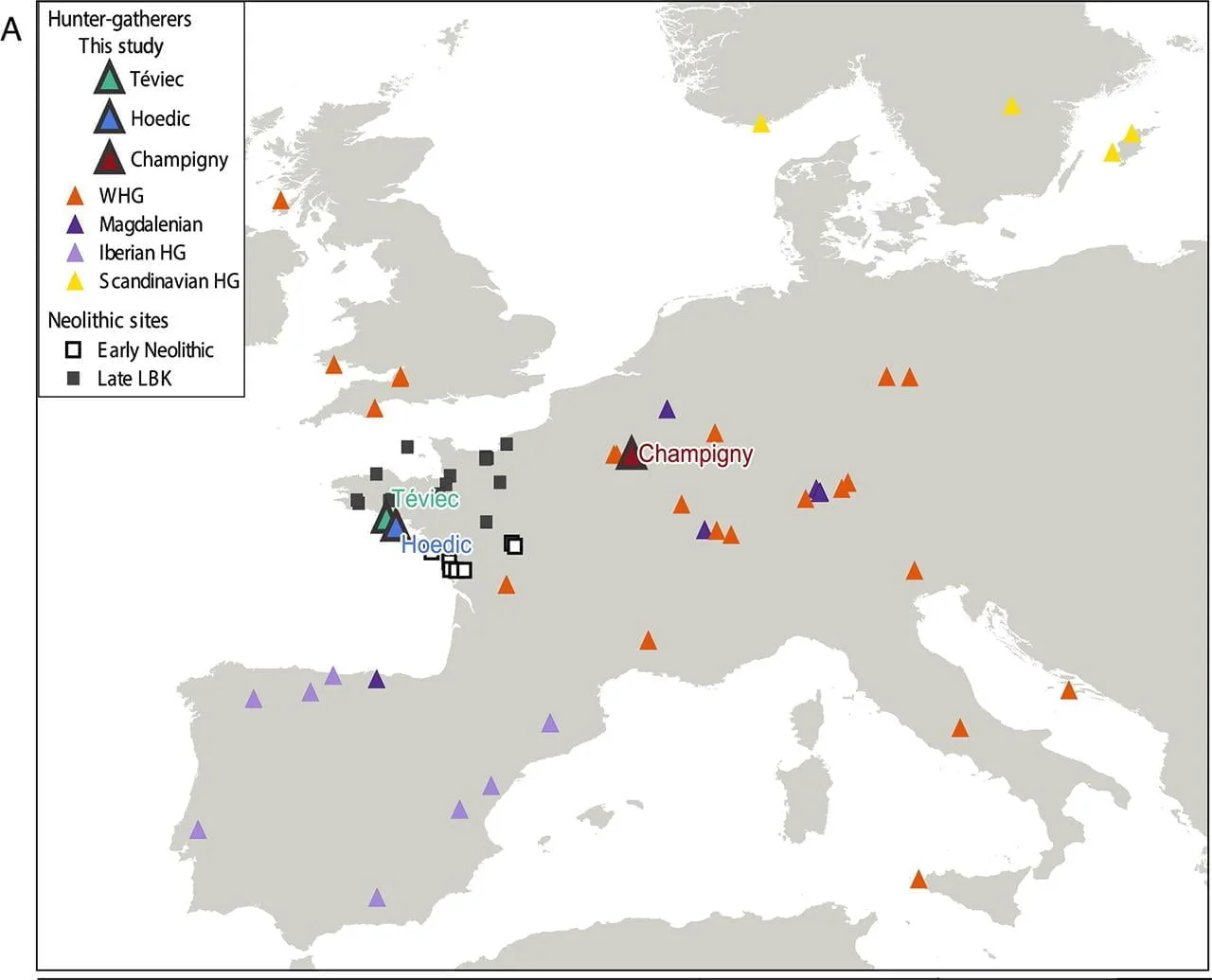

Map indicating the location of Paleolithic and Mesolithic sites used for comparative genetic analysis. Credit: Simões et al., PNAS (2024)

The genomic analysis also challenges earlier theories that suggested hunter-gatherer communities assimilated women from neighboring farming communities. Instead, the study indicates that these groups primarily interacted and interbred with other hunter-gatherer populations, rather than with farmers.

“Our genomic analyses show that although these groups were made up of few individuals, they were generally not closely related,” says Simões. “Furthermore, there were no signs of inbreeding.”

One intriguing aspect uncovered by the study is the presence of strong social bonds within these ancient communities that transcended biological kinship.

Even in cases where individuals were buried together, such as women and children in the same grave, they were often found not to be biologically related. This suggests the importance of non-biological relationships and social connections that persisted even after death.

Dr. Amélie Vialet from the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in France, a co-author of the study, says: “This suggests that there were strong social bonds that had nothing to do with biological kinship and that these relationships remained important even after death.”

Professor Mattias Jakobsson from Uppsala University, who led the study, underscores the importance of this research in understanding the dynamics of ancient populations: “Our study provides a unique opportunity to analyze these groups and their social dynamics.”