Zach Schonfeld on a Family Not Unlike the Corleones

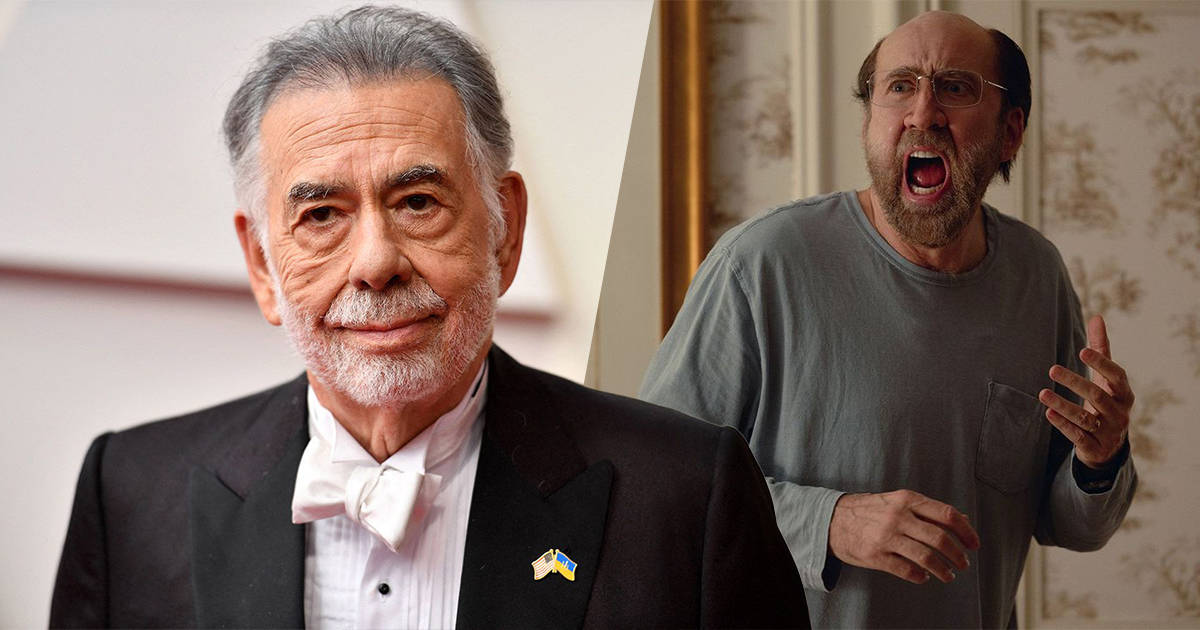

To study Nicolas Cage’s rise is also to study Francis Ford Coppola’s fall from grace. You cannot write about one without the other. In the early to mid-80s, their trajectories were almost conversely linked—Cage siphoning power from his uncle’s desperate need to work, like Michael Corleone growing stronger with the Godfather’s faltering health.

Except it wasn’t Coppola’s physical health that was faltering. It was his career and finances. In simplest terms, Coppola helped launch his nephew’s career by giving Cage three significant early roles: Rumble Fish, The Cotton Club, and Peggy Sue Got Married. Two of those were teen pictures. Coppola was making multiple teen pictures in quick succession largely because he needed money. Coppola needed money because the flop of his 1982 dream project, One from the Heart, had plunged him and his studio into deep debt. See how it’s all connected?

Forced to work himself out of debt, Coppola pivoted to a nimbler style of filmmaking, making four feature films in four years (by contrast, he directed just four during the entire 1970s) and calling upon a new generation of stars, such as Ralph Macchio and Matt Dillon. Nestled in some dark crevice of that new generation was Coppola’s own nephew.

Even as a child, Cage had a complicated relationship with his uncle’s fame and fortune. He was eight when the indelible gangster epic The Godfather established Coppola as an icon of the New Hollywood era. Tension grew between Francis and [Cage’s father] August. Francis sent Cage’s family a package of Godfather promotional T- shirts, but August wouldn’t let Cage wear one. Cage eventually saw the film and was aroused by the scene in which Michael’s Sicilian bride undresses while kissing him. When The Godfather Part II came out, August took him to see it, but said, “Don’t tell your uncle we went to see the movie.” When production began on Apocalypse Now, “Francis wanted us to go to the Philippines, because we were very close with his kids,” Christopher recalls. “And my dad said, ‘Absolutely not, are you kidding me? They’re in school.’ He refused.”

Cage once described the Coppola family as “loaded with grudges and passion”—perhaps not unlike the Corleone family. Growing up, Coppola had always been conscious of Cage’s father’s good looks and academic success. August was the golden child: brilliant, handsome, passionate about the arts. Francis, five years younger, was a comparably mediocre student.

“He was like the star of the family and I did most of what I did to imitate him,” Francis recalled in a 1983 interview. “Tried to look like him, tried to be like him. I even took his short stories and handed them in under my name.” Coppola liked to imagine that his brother would be a famous novelist someday and he would be a playwright. Even Coppola’s screen credit was modeled after August: he went by Francis Ford Coppola, middle name and all, because his brother was August Floyd Coppola.

The Godfather changed the family dynamic for good. Francis’s success and fame far eclipsed his brother’s achievements in academia. The Coppola family was full of artistic accomplishment, but suddenly everybody else’s careers seemed to orbit around Francis. Talia Shire was a gifted actress whose greatest acclaim arrived when her brother cast her in The Godfather. Carmine Coppola was a long-frustrated composer—frequently unemployed, resentful of those more successful than him—but finally won an Academy Award when his son hired him to write music for The Godfather Part II.

Cage once described the Coppola family as “loaded with grudges and passion.”

Between 1972 and 1974, Francis directed three masterpieces back to back—The Godfather, The Conversation, and The Godfather Part II—two of which won Best Picture. These years of greatest acclaim coincided with rough years for Cage’s family. August was raising three sons on an academic salary; his wife was enduring long periods of hospitalization. They divorced by 1976.

August poured himself into his work, which grew ever more eccentric. He wanted to be a great American novelist—one who wrote books, not screenplays. “That was important to him, to be recognized as a novelist,” says Cage’s brother Christopher. In 1978, he published an experimental erotic novel called The Intimacy, about a man and woman who choose to live in total darkness in search of “a rehabilitation of the soul.” The book was the culmination of the professor’s obsession with touch, and it was filled with passages of gooey erotic exploration (typical sentence: “He pumped all the harder, his testicles slamming up against her, his temples aching”).

While the book apparently resonated with August’s female admirers, it was not a success. By 1985, it had sold fewer than 2,000 copies.

“We lived with him while he was writing it,” says [Cage’s brother] Christopher Coppola. “He thought the book would be a huge success. It was a major flop. It hurt him deeply. He got mad when they wanted to capitalize Coppola and make August small and was furious.”

Such blow-ups were common in the household. “We’re very difficult,” Christopher says. “My dad was incredibly high-maintenance. Little things could happen that would trigger him and you would wonder why.”

The Godfather changed the family dynamic for good.Meanwhile, The Intimacy fermented bitterness when some members of the family believed August had based a villainous character on Francis. As Christopher puts it, “That book has a lot of ugliness around it.” Though the book jacket stated that August was working on “two succeeding novels,” he never published another.

By 1974, Francis Ford Coppola was among the most celebrated and well-paid filmmakers in America. Soon he owned a 22-room Victorian mansion in San Francisco, a Manhattan apartment in the Sherry Netherland Hotel, and a Napa Valley estate and adjoining vineyard.

Into this world of fame and fortune stepped the adolescent Cage—always a visitor, never a belonger. Cage and his brothers spent summers at Uncle Francis’s house, where they encountered Hollywood legends walking the halls. The San Francisco house had a screening room, and once, at 14 or 15, Cage was permitted to attend an early screening of Apocalypse Now, which amazed him with its horrific scope.

“He had a long conversation with Dennis Hopper, who was there at that screening,” says Apocalypse Now co-producer Fred Roos, a longtime Coppola collaborator. “He was so impressed that Dennis Hopper would talk to him about movies and art and acting. It was a watershed experience for him.” When Cage told Hopper that he liked classical music, Hopper took the boy seriously and recommended an opera by Prokofiev.

“You were great, Francis, but I hold the mantle now.”

At the same time, Cage’s relationship with his famous uncle was straining under the weight of jealousy and resentment. The stories Cage has told are grandiose enough to have been rejected from a Godfather screenplay. A few choice anecdotes:

1. Cage, around 12 or 13, was in the backseat of his uncle’s car. Coppola was driving over the Golden Gate Bridge, listening to the Beatles song “Baby, You’re a Rich Man.” “I was thinking, ‘Yeah, he really deserves to listen to this, doesn’t he?’” Cage later told the writer Eve Babitz. “He was right at the height of Godfather II, and I vowed to myself that one day I’d be able to listen to that song, too, as a reward to myself.” (When Valley Girl was a hit, Cage fulfilled this wish by taking his Triumph Spitfire for a joyride on Sunset Boulevard and savoring every word of the tune.)

2. Another car ride with Coppola, late 1970s. Cage told his uncle, “If you want to see acting, give me a screen test and I’ll show you acting.” No answer. His uncle simply ignored him.

3. Cage and his father were at his uncle’s house. August and Coppola were talking about something James Joyce supposedly once said to his literary idol, Henrik Ibsen: “You were great, but I hold the mantle now.” Years later, after Valley Girl, Cage was at his uncle’s house again. “He was lighting a cigar and I just said it: ‘You were great, Francis, but I hold the mantle now.’ He got upset and flustered,” Cage recalled in 1996. (Cage reflected that there is “a fundamental competitive edge amongst the men in my family.”)

Cage has insisted these stories are true (this seems like a place to note that multiple attempts to interview Francis Ford Coppola for this book were not successful), but they feel like origin myths, peaks into the damaged psyche of someone who grew up hungry and ambitious in the shadow of an artist whose ambitions were fulfilled beyond anyone’s imagining.

“We were the Southern Coppolas, sometimes called the poor Coppolas, because we weren’t rich,” Christopher reflects. “So he had a lot of anger. He wanted to make it big. And he did, because he’s goal-oriented.”

Cage grew up in proximity to vast wealth but not with vast wealth, and there lay the distinction. Like many Italian-American patriarchs, Coppola was known for his hospitality—cooking extravagant dinners, entertaining guests. Cage was often a beneficiary of this hospitality. But when the young Cage spent a year living at his uncle’s house—riding around in his uncle’s cars, marveling that his cousins had a movie theater in their basement—he stewed in the knowledge that this opulence did not belong to him. He vowed that someday he would return and buy a palatial mansion in San Francisco of his own. “I said, ‘You know what? I am going to get back. I am going to get even somehow.’ And I think I turned into Heathcliff,” Cage later recalled, referring to the jealous hero of Wuthering Heights.

But Cage’s true revenge was not in accruing wealth of his own. It was in relinquishing the family name, a proud name stretching back generations. Surely Coppola of all people understood that this was not personal; it was strictly business. Still, he did not like his nephew’s decision. When Valley Girl came out, Coppola sent Cage a congratulatory telegram. He signed it: “from Francis Cage, Eleanor Cage and all the other Cages.”