Liam Neeson is nothing if not paternal. I learned this in 1998, as a young woman in my 20s, when I met the actor in Los Angeles for an assignment.

Neeson gamely went shopping at trendy boutiques, folding his towering frame into tiny dressing rooms — a good sport about every ask. We ate lunch and dessert. Then, as the day wrapped up and the work concluded, he asked me about myself, something actors rarely did, most of them eager to leave the journalist behind as quickly as possible. As we waited for the check, I briefly lamented my current romantic entanglement. Neeson leaned back, listened and, when I was done whining, offered piercing counsel about my unsuitable suitor.

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

“Well, Allison, it sounds like he’s not the sort you’d want to be raising babies with.”

As he drove me back to my hotel, Neeson spoke lovingly of his wife, actress Natasha Richardson (who, in 2009, would pass away from a head injury sustained in a skiing accident), of the poetry to be found in a marriage, of the capabilities of strong women, of his three brilliant sisters and his steadfast mother, and of the long tradition of generations of women compromising for men who don’t deserve it. By the time I got out of the car, my would-be boyfriend was toast.

Neeson has been acting since age 11, when he accepted a part in a school play to impress a girl back in his native Northern Ireland, and he has always baked compassion and attention into everything he does, from performances to personal relationships to parenting. He was raised to believe that everybody mattered and that making things right was well worth the effort.

On top of that, he says, “there was a war going on where I lived for 30 years.” As a result, Neeson is not a person who half-steps or shrugs or takes any kindness for granted.

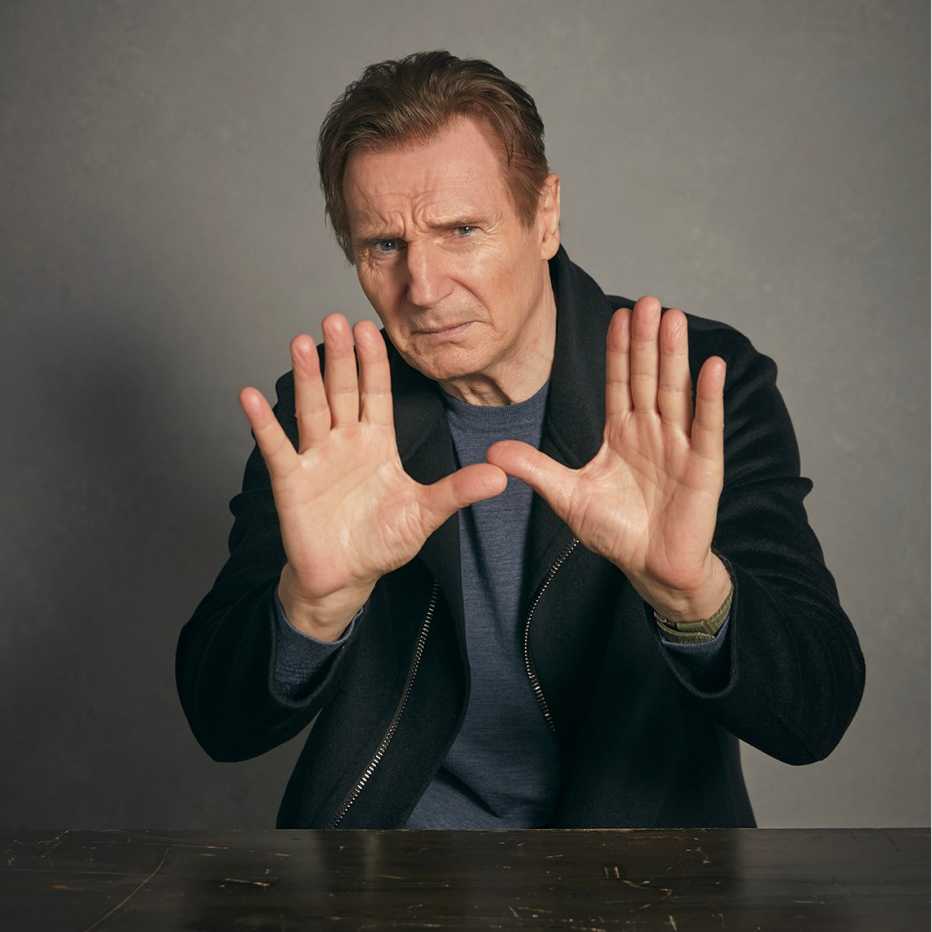

JOHN RUSSO

Tall, with hands as big as bread loaves and a gravel-bed brogue of a voice, Neeson could enter any space and make others uncomfortable for sport. Instead, he does the opposite.

He strives to create solace in his orbit, to embrace, to help — holdovers from his modest, working-class roots, where getting by required ceaseless effort without complaint. It’s little surprise that, over the decades, Neeson has played every variety of father figure on offer: all men who do their level best to stand up and lead as they reckon with their onerous, flawed humanity.

There was Holocaust hero Oskar Schindler; Scottish folk hero Rob Roy; the tormented and tenderhearted Jean Valjean of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables; and Jedi Master Qui-Gon Jinn (the first Jedi in the Star Wars universe to manifest consciousness after death). Neeson has even voiced the animated lion in The Chronicles of Narnia series, playing no less a paternal figure than God himself. He has also portrayed Zeus (Clash of the Titans, 2010).

And then there’s Taken — the revenge thriller in which Neeson becomes a stand-in for all righteous-warrior dads who’ve ever fantasized about doling out justice on behalf of their wronged daughters and wives. It’s a film turned franchise that, thanks to Neeson’s committed, elevated performance, lifted what could have been a standard B-movie run-and-gun to the action-film canon and gave birth to a whole fresh genre of geri-action movies — a development that tickles Neeson no end.

“If I’m sent an action script,” he tells me, “I’ll say to my agent, ‘There’s seven fight scenes. I kill a bunch of guys that need to be killed. Do the producers know my age?’ ”

Which is not to suggest that Neeson intends to retire. When you come from a place where strife is the norm, where circumstances remind you every day that life is cruel and random, you don’t quit when you’re ahead, even if you are entering your 70s.

His brush with death in 2000 — after a hellish motorcycle accident that broke his pelvis and had doctors not expecting him to last the night — only reinforced what Neeson has always known: You seize the day, and you do it with the awareness that you are less special than lucky.

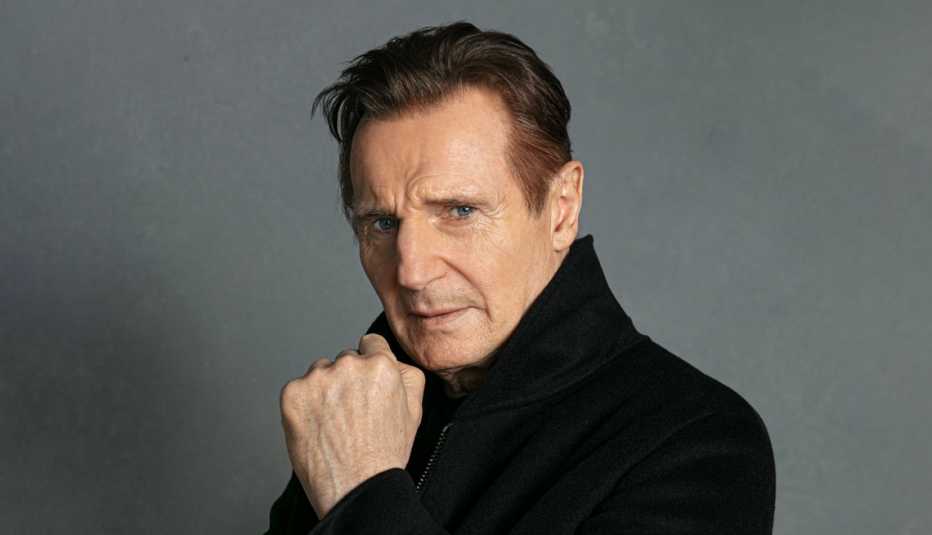

JOHN RUSSO

Memory is exactly what I wanted to talk about with you. What remains with us, what it says about a life. Memory is also the title of your latest film [out April 29]. In the film, you play a professional assassin, and a fellow assassin says to you, “Men like us don’t retire.” Do you think about slowing down at all?

Allison, are you saying I’m too f—— old to be acting — is that what you’re getting at? Come on, tell me the truth.

I would never. But the stunts, the physicality — it’s a lot for anyone.

The stunts I leave to the stuntman. The fighting I do myself, and I keep reasonably fit for that. You know, this movie Taken that we made 14 years ago, this tiny little European thriller, which I thought was going to go straight to video — I think it came out number 3 over the weekend when it released.

It became very, very successful. Hence, Taken 2 and Taken 3. And because of that, they’re still sending me action scripts, you know? They wanted me to do one with Jackie Chan, which when I read it, I thought, Well this would be tough for a 22-year-old to do, let alone a 69-year-old who’s going to be 70 this year. That’s the only one I turned down.

Your hit man in Memory is suffering from the beginning stages of dementia. In the first scene, we see your character misplace his keys after deftly garroting a man in a hospital.

When I first read it, that scene grabbed me immediately. I thought, This is going to be very interesting to play, you know? I did quite a bit of research on Alzheimer’s. It was very hard to watch the TV documentaries and read the books I read.

My elder sister, she has a very close pal who is suffering from dementia, and he cannot remember stuff from five, 10, 15 minutes ago. So, in Memory I work in little bits of stammering or clumsiness that grabs people in the audience who know someone who’s suffering from it, from dementia or Alzheimer’s, but I wanted to keep it very, very subtle, because it could become jokey if I overdid the dementia. This film is supposed to be a piece of entertainment, so hopefully there’s a few thrills and spills. But there is a deeper story to be told.

What are your most vivid memories from childhood?

I lost my mother recently. She was 94. She’d worked 34 of those years as a dinner lady in a girls school. I think about her every day, and it’s always a different memory. Tiny, tiny little things. Gestures.

The way she would look at you. I was an amateur boxer as a kid, from the ages of 9 until 17. There’s guys I boxed with who died tragically during the Troubles in the north of Ireland. I remember them.

This past weekend was the 50th anniversary of what is known as Bloody Sunday, when British paratroopers murdered 13 of our people in the streets of Derry, in the north of Ireland. And I remember the next day, when everything was incredibly quiet and very, very sinister. I lived in Belfast during a lot of that. And I think back on it now. Why did I survive that?

If you’re raised in those circumstances, surrounded by potential political violence, it really shapes you moving forward. It lodges in the bone.

It does. Maybe we shouldn’t talk about this, but when I was growing up, we had a neighbor next door — we lived in these little terrace houses — and I remember hearing her being beat up by her drunken husband every weekend.

He’s dead now. But that’s a memory I am still coming to terms with. I’m talking 50 years ago. It’s kind of a post-traumatic stress disorder. I don’t know if it has scarred me, but it has definitely formed something of my character. Maybe you’re right — maybe even when I play these violent roles, I’m trying to bring some quality of redemption or justice.

It seems like you dance between brutality and benevolence.

Savior, Jedi, Dad, Hero

AARP’s chief film critic traces Liam Neeson’s path

EVERETT COLLECTION

Schindler’s List (1993)

In the year’s blockbuster best-picture winner, Neeson played industrialist Oskar Schindler, who risked all to save more than 1,000 Jews during the Holocaust.

Star Wars: Episode 1 — The Phantom Menace (1999)

As Qui-Gon Jinn — second only to Yoda for mentoring Obi-Wan Kenobi — he gives his life to fight the Sith Lord. Though there’s talk of his revival!

Love Actually (2003)

He poignantly portrays a grieving widower who helps his shy stepson court a classmate — and who finds a new love himself (Claudia Schiffer).

Taken (2008)

His retired CIA character hunts the kidnappers of his teen daughter. This film and its two sequels grossed almost $1 billion at the box office: Neeson now rules the action-flick genre.

Ordinary Love (2019)

As a husband supporting his wife through a year of cancer treatment, he crafted an immortal portrait of romance that will not die.

— Tim Appelo

I try to. People say, “Oh, you were a boxer. You must be used to violence.” With boxing, there was a referee, there were judges. We trained three to four days a week with this big Irish priest. There was respect, especially after a fight. You’d go and hug your opponent, and he’d hug you. Yes, you’re trying to punch each other’s head off with gloves, but there’s something else, too — dare I say it: the word “love,” ya know?

When was the last time you were afraid of anything?

When you’re young, you think, Oh, nothing will ever happen to me. When I think back on that now, the stuff I did — I wasn’t a rebellious kid, by any means, but I loved acting so much, I used to hitchhike up to Belfast after I finished a day’s work as a forklift truck driver, just to rehearse a play.

Crazy, just crazy. Why did my parents let me do that? [Laughs.] Now I’m a father of two sons [Micheál, 26, and Danny, 25]. As a parent, you’re always thinking, They should’ve been back 10 minutes ago — what’s happened? My dear friend Meryl Streep came up to visit Natasha, my late wife, and myself when Micheál was 6 months old.

He was lying on his cot, asleep, arms above his head, and she said, “That’s good. He’s not curled up. He’s comfortable and feels at home.” And I said, “Thank you, Meryl. That’s very sweet.” And then, as we were heading down the stairs, she added, “You both realize you’re hostages for the rest of your life, right?” [Laughs.] And she was absolutely correct, absolutely correct.

How do you unwind?

I have a few acres upstate. I have a walled garden where we grow vegetables. I have three apple trees. Sometimes these trees decide to bear fruit. Then they’ll take two years off and say, “F— you, we’re chilling.” But this past year all three trees produced lovely, lovely apples. Just to walk past them, pull on an apple, eat it by my back pond stocked with koi a neighbor gave me — I’ll feed the fish; they take the food from my fingers — it gives me an incredible amount of pleasure.

That sounds idyllic. Are there goats or chickens about?

No, no. Long ago we tried chickens, and they stopped laying. Someone suggested getting a cock and putting it in there. I got this little cock, and every time I went in to check on the hens, this cock would fly in my face. Every morning. And I thought, I’m going to kill this f—–. I told Natasha, I said, “Darlin’, we can’t do this. This cock is putting the fear of God in me.” We got rid of the chickens. We didn’t kill them — we gave them away.

You’re also an avid fisherman. When did that start?

I was doing a film called Nell with Jodie Foster and Natasha, and we were in North Carolina, shooting at this little log cabin beside this lake. And the props lady said, “Would you like a fishing rod?” And I said, “Sure.”

She had just come off Robert Redford’s lovely film A River Runs Through It, so she taught me how to cast with this split-cane fly-fishing rod. And I literally got hooked. Between setups, I would dash down to the lakeside, get my fishing rod and practice casting. That’s 28 years ago now — God, talk about memories.

It seems like you enjoy solitude.

During the lockdown, I was in heaven. I read something like 30 books. I was a pig in s—, totally content. I was very aware of millions of Americans wondering where their next meal would be coming from. I was very, very aware of that. But there I was upstate. I wasn’t exactly Nero, but I was very content.

What were you reading?

A lot of crime fiction. I got into Nordic noir big-time. Jo Nesbø, Henning Mankell. I just couldn’t get enough of these thrillers. And then I’d think, OK, I’m Irish. I have to tackle Ulysses for, like, the fifth time. I must finish Ulysses and Crime and Punishment and War and Peace. So, I did — I managed to read those three books to offset all the crime novels. I can’t go to sleep at night unless I have read something.

Do you want to write a book?

I don’t. I’m just not a writer. That would terrify me, to wake up every morning and look at a blank page of paper and know I have to fill it to put a meal on the table.

You mentioned your children. What have they taught you about yourself?

Well, it’s a continual process, isn’t it? Sometimes you see in your kids a flash of their mother or a flash of your grandmom, and it might last only seconds, but you see the connection.

I always think of my friend Gabriel Byrne. I’ve known Gabriel for over 40 years. Ages ago, when his little boy was 2, I went to visit him. He had rented a house because he was doing some movie, and we were sitting at the swimming pool, and I was watching this kid, this beautiful little creature with long blond hair, running around the pool naked.

I said, “Gabriel, what’s that like?” And he said, “I’ll tell you. I was there when he was born, and when he came out, I realized my place in the universe.” I was there for the birth of my two boys, and that’s exactly what happened. Something shunted into place, a continuum. It’s strange and miraculous and kind of frightening, too.

In some ways, it seems so simple, but it’s really everything.

JOHN RUSSO

Yes, exactly.

These are interesting times. Are you optimistic about the future?

I’m very concerned about what’s happened in Ukraine. And England and this whole Brexit business is an absolute shambles, and it’s hurting people. It’s really hurting people. I hope some levelheaded politicians will see the light. We’re Mr. and Mrs. Gloom and Doom, aren’t we?

Well, my heritage is Scots Irish, so there’s no way around it.

Do you know what Irish Alzheimer’s is?

You forget everything but the grudges.

Exactly! [Laughs.]

Looking back on your life, what’s left that you want to do?

Ohh, to play King Lear, darlin’. On the stage. [Laughs.] Not. No, I’ll be very honest, Allison. I turn 70 in June, and they’re still sending me scripts to do. Some of them are interesting. Others aren’t so interesting, but I’m still getting work, and I’m very blessed, very lucky.

Allison Glock is a writer and executive producer for ESPN and NBC’s The Blacklist. Michael Douglas was her most recent cover subject for AARP The Magazine.