![]()

January is the dumping month for movies. Any film with award aspirations has been released during November and December to qualify for Oscar nominations, while tentpole pics hit screens during the blockbuster-making holiday season.

Those first few weeks of the year are when movies that have gotten lousy scores in test screenings or have been gathering dust on studio shelves get their day, with the expectation that they’ll hang around theaters no longer than the popcorn sticking to the floor.

The box office takes the deepest dive on Super Bowl weekend, so it was a Hail Mary pass when on Friday, Jan. 30, 2009—two days before nearly 100 million Americans would watch the Pittsburgh Steelers defeat the Arizona Cardinals—20th Century Fox released Taken.

The action flick had a paltry budget of $25 million and a familiar revenge plot—former CIA agent Bryan Mills sets out to rescue his daughter when she’s kidnapped in Paris by a gang of sex traffickers. “That release date took guts,” says Paul Dergarabedian, a box-office analyst for Rentrak, a provider of viewership data.

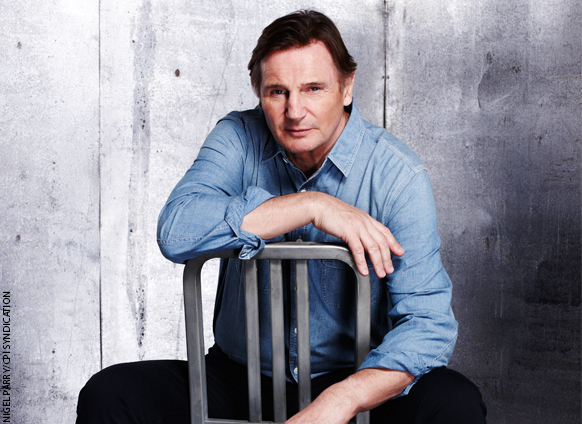

“It went against the grain. What you typically see opening on Super Bowl weekend are romantic comedies that are aimed at a female audience.” Even the movie’s star, a then 56-year-old Liam Neeson, had thought that the movie—what he describes as a “very, very basic, simple storyline”—would stay under the radar.

It didn’t. Opening on some 3,200 screens, Taken nabbed the No. 1 spot at the box office, earning a remarkable $24.7 million. Even Fox Chairman and CEO Jim Gianopulos was astonished. “We’d screened the film and went, Wow, this is really great,” Gianopulos says.

“The release calendar gets very crowded during the holiday season, and while we knew what we had, we also knew we needed word-of-mouth for the movie to get momentum. So we weren’t surprised that the movie turned out to be a success, but we were very surprised by the extent of it that first weekend.”

Taken would go on to earn $145 million in domestic box office receipts and nearly $84 million internationally, making Liam Neeson an action star and giving rise to a franchise.

Three years later in Taken 2, protagonist Bryan Mills and his estranged wife (Famke Janssen) are kidnapped in Istanbul.

That film would earn $376 million worldwide. And on Jan. 9, the final Taken installment opens; this time Mills is on the run after being framed for the murder of his ex. Neeson, 62, is one of Hollywood’s highest-paid stars, on track to earn a reported $50 million for Taken 3.

“I laugh at it,” he says. “It’s not that I laugh at the franchise itself or the position I find myself in. I just laugh at the ridiculousness of life.”

At 6 feet 4 inches, with the slightly off-kilter features of the amateur boxer he once was (he broke his nose in a match at 15), Neeson always had the rough-hewn good looks of an action hero. If it’s improbable that it took until late middle age for him to achieve that mantle, Neeson says that timing is just right.

Had Taken come along in his 20s or 30s, he says he would have screwed it up (he uses a saltier word), and typecasting might have made it difficult for him to be believable playing the towering historical figures that have defined him as one of the greatest actors of his generation.

“I certainly wouldn’t have been able to do Schindler’s List or Rob Roy or Michael Collins,” he says. Besides, he adds, “I think that what added to the popularity of Taken was the fact that I’m an elder guy. I’m a father, so I can totally empathize with how Bryan Mills reacts when his kid is in danger.

I think that comes across.” What’s left unsaid is that audiences also know Neeson has dealt with a devastating loss—the death of his wife, actress Natasha Richardson, after a 2009 skiing accident.

“He’s lived through a lot,” says Olivier Megaton, who directed Taken 2 and Taken 3. “You feel his humanity and his struggle. He knows life can be very hard, bad things happen, and you just keep on fighting.”

In real life, Neeson has some traits you’d never associate with an action hero. He’s afraid of heights, for one thing. For another, he had to give up boxing because he blacked out during bouts.

And his idea of a good workout is a 90-minute walk through Central Park or near his home in upstate New York, a habit he took up as part of his rehab when he had a near-fatal motorcycle accident in 2000. (But make no mistake, these are power walks.

“I’ve done some of those walks with Liam,” says actor Aidan Quinn, a good friend and godfather to Neeson’s younger son, Daniel. “And the man moves; his stride is fast.

These are deep-in-your-adductors, heart-pounding walks.”) And Neeson is a voracious reader who’s always juggling a few books.

He’s reading The Richard Burton Diaries and a crime novel by the British writer John Burdett, plus a thriller by Scandinavian author Kristina Ohlsson.

Introverted and bookish, Neeson might be a very different person from Bryan Mills, but, says Janssen, “If you were in danger, Liam is the person you’d want to have rescuing you.” Actress Laura Linney agrees.

She and Neeson are close friends—she starred opposite him in the films Kinsey, The Other Man and Love Actually, and on Broadway in The Crucible. “I always feel safe when I’m around Liam,” Linney says. “Some of that is his strength and masculinity and his great looks. But beyond those superficial reasons are deeper ones, like his devotion as a friend.

It’s not the big heroic gestures; it’s the little ones. Liam keeps in touch; he’s aware of what you’re going through. You feel appreciated by him.” When Linney wed, just four months after Richardson’s death, Neeson walked her down the aisle.

Women in large numbers are smitten with Neeson. A big part of the success of the Taken movies, says Gianopulos, is that they draw a far more sizable female audience than is typical of action pictures. But to paraphrase a sentiment first applied to James Bond, if women want to be around Neeson, men want to be him.

“There are some leading men who piss other men off and make them angry, jealous and uncomfortable,” Linney says. “Liam isn’t one of them, and I think that’s because he has an innate modesty and an innate decency that’s comforting. Everyone—men and women—feel better when he’s around.” That’s certainly true for Megaton.

“The first time I met Liam,” he recalls, “he said, ‘If you need me, I’m here to protect you.’ When you make a movie, you have a million problems a day, and Liam wanted to be there for me.”

In fact, men’s admiration for Neeson can undermine his ability to play a convincing tough guy in real life. Maggie Grace, who portrays Neeson’s daughter in the Taken trilogy, was 24 when she made the first film and, she says, “trying to get over a boy who broke my heart.”

Neeson, with a combination of humor and paternal concern, called the guy, leaving a version of the speech he made famous in Taken: “I have a very particular set of skills, skills I have acquired over a very long career. Skills that make me a nightmare for people like you…. I will look for you, I will find you, and I will kill you.”

“We tailored the speech to scare the living beejesus out of the guy,” Grace says. “But it backfired when he figured out it was really Liam and not an amazing Liam impersonator. He was so excited.

‘Liam Neeson called my office! That’s the coolest thing ever! Do you have a video of it?’ Liam and I laughed so hard.” Still, even if that prank call failed to intimidate, “What girl,” says Grace, “doesn’t want a father figure like Liam freakin’ Neeson to watch out for her now and then?”

Neeson has made some 70 movies, 15 in the last three years alone. In April he stars as an aging hit man in Run All Night, has a small part in the comedy Ted 2, and then the title role in A Monster Calls, an adaptation of the children’s fantasy novel.

Clearly, even if that reported $50 million Taken 3 windfall is off by a few mil, he’s not doing back-to-back flicks for the paycheck. Instead Neeson works nearly nonstop because, he says, “I absolutely adore the business” and because people ask him to. “I get a kick out of complete strangers getting in touch with my agent or sending me a script that they want me to be in,” he says.

“There’s a part of me that’s like the little boy in a toy shop thinking, Oh, I want to have that, I want to have that, and I want that. Can I do both those jobs? Can I do all three? And you know, I also want to please everybody and do it all.”

That work ethic was forged in Neeson’s modest upbringing in the Northern Ireland town of Ballymena. “I’m not going to give you some sob story about how we were at death’s door because of poverty,” he says, “but we were very, very working class.

My mother worked as an assistant cook. My father had, let’s say, long periods of unemployment and eventually became a grammar school custodian.

So money was tight.” Neeson began working on construction sites when he was 15. “You got paid on a Thursday, and you came in and handed your wages to your mom,” he says. “It was a great feeling of achievement. It does make you feel grown up.

It does make you feel responsible. You realize your place in the world when you have a job, and when you get paid in that little brown envelope, it connects you to the rest of working humanity, and that just felt very, very comforting.”

He learned another lesson about humanity from his grandfather, a steam-engine driver. Once he retired, he’d scan the newspaper every morning to see who had died.

“Inevitably he’d find some name, say O’Rafferty, and he’d think, I wonder if that was the guy I worked with 30 years ago,” Neeson says. “He’d find out where this gentleman was being buried, and he’d walk there. He was a fantastic walker. When I was 6 or 7 or 8, he’d sometimes make me go with him, and we’d walk for what seemed like miles.

I remember standing around those graves, just the priest, an altar boy, my grandfather and me while some prayers were said. That became my grandfather’s later-life vocation. He believed every life means something. Like Biff Loman’s mother says to her son in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, ‘Attention must be paid to such a man. Attention must be paid.’ ”

Neeson began acting when he was 11, attracted to the stage because a girl he liked who had “skin of alabaster and cherry-red lips” was starring in the school play.

He kept acting in school productions and later attended Queen’s University in Belfast. Interested in becoming a teacher, he took classes elsewhere, but those studies didn’t hold his interest, and he dropped out to pursue acting. He joined the Lyric Players’ Theatre in Belfast and two years later began performing with Dublin’s famed Abbey Theatre.

At 28 he got his first high-profile movie role, Sir Gawain in Excalibur. The 1981 film starred Helen Mirren, and the two began a romance that lasted four years.

“I fell in love with Helen Mirren,” Neeson recalled on 60 Minutes. “Oh my God. Can you imagine riding horses in shiny suits of armor, having sword fights and stuff, and you’re falling in love with Helen Mirren? It doesn’t get any better than that.”

After that action fantasy, Neeson had supporting roles in movies such as The Mission, an 18th-century adventure starring Robert De Niro, and played opposite Cher in Suspect and Diane Keaton in The Good Mother.

Fans of Sonny Crockett and Rico Tubbs might recall Neeson’s portrayal of a former member of the Irish Republican Army in a 1986 Miami Vice episode.

His first starring role was the 1990 fantasy thriller Darkman, and in 1993 he was cast as Oskar Schindler in the masterful Steven Spielberg Holocaust drama Schindler’s List, which led to an Academy Award nomination.

But his performance left him dissatisfied. (“I thought the film was quite extraordinary except for myself,” he has said.

“I didn’t own the part. I didn’t see enough of me in there.”) He would go on to win critical raves playing an 18th-century Scottish Highlander in Rob Roy, the Irish revolutionary Michael Collins and sex researcher Alfred Kinsey in Kinsey.

There were lots of other high-profile roles: in Martin Scorsese’s Gangs Of New York and Woody Allen’s Husbands And Wives, in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace and Batman Begins.

Straddling genres, he did Westerns (Seraphim Falls) and comedies (A Million Ways to Die in the West and Gun Shy), battled the bad guys on a submarine (K-19: The Widowmaker) and a plane (Non-Stop), and fought off wolves (The Grey) and deviant drug lords (A Walk Among the Tombstones).

Leaving his snarling demeanor aside, he voiced Aslan the lion in the Narnia movies, and the good cop and bad cop in The Lego Movie.

Neeson says when he catches some of his old movies as he’s flipping through TV channels, he winces. In Excalibur, for example, “I’m chewing up the scenery,” he says, then adds, “God knows I’ve done some not-very-good movies. But it’s always a learning curve, always.

I always try and come away from the experience having learned something or some things.” His more recent acting is less likely to make him cringe. “Overall I think I’m a much better actor now that I’m older,” he says. “I feel very comfortable in front of a lens and nothing throws me off.

Be I in a suit of armor with a false beard, on horseback being chased by dragons or looking at a Russian terrorist: It’s OK; this is the story. This is what I have to do. And I like to think I’ve minimalized my acting over the years, meaning I’ve achieved something whereby less is more.”

Megaton says Neeson is very precise in his acting. “He likes to go very far into the realities of his character,” the director says. “We had an ex-CIA agent consulting on Taken 3, and Liam would ask lots of questions, like how he’d walk into a room when he knew that inside there were people with weapons.”

There’s a favorite Samuel Beckett quote that Neeson and his late wife shared: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” Neeson and Richardson met in 1992 after being cast in the Eugene O’Neill play Anna Christie on Broadway.

“She and I were like Astaire and Rogers,” Neeson told 60 Minutes. “We had just this wonderful kind of dance, free dance on stage every night, you know?” They wed in July 1994 at the couple’s farmhouse in upstate New York; their son Micheál was born in 1995 and Daniel the following year.

“They were a fantastic couple,” Quinn says. “Natasha was always organizing some great gathering at their place. The parties they used to have once or twice a year were legendary.

Natasha would take care of every detail. She was a great chef; there would always be great wine and spirits, good music. She loved bringing people together.

Natasha had her shy side, but she was much more of an extrovert than Liam, and when it came to socializing, she was the motor.”

Whenever Neeson or Richardson did theater, they kept the Beckett quote in their dressing room as inspiration.

“You’ve come offstage,” Neeson says, “you’ve done a lousy performance for whatever reason, and you get a chance to go on stage the next night and the night after that for four or five months.

You make it better, but you have to be there. You have to come back to the plate again. You have to keep always coming to the plate.”

For Neeson the quote resonated beyond acting. “You think all things are lost, but it’s not lost,” he says. “There’s always hope.” It was a belief he needed to draw upon in March 2009.

Neeson was in Toronto filming the movie Chloe when Richardson called from a Quebec ski resort where she was on vacation with Micheál. She’d fallen and hit her head coming down a beginner slope. “Oh, darling,” she said to Neeson, “I’ve taken a tumble in the snow.”

In fact, although she didn’t know it, Richardson had suffered a traumatic brain injury. By the time Neeson reached the hospital in Montreal, X-rays showed she was brain-dead.

The couple had a pact: If either of them was ever in a vegetative state, the other would pull the plug. Neeson gave the directive. Richardson’s heart, kidneys and liver were donated, “so, she’s keeping three people alive,” Neeson says. “And I think she would be very thrilled and pleased by that.”

Days after Richardson’s funeral, he was back on the set of Chloe. He wanted, he says, to be a good example to his sons, then ages 13 and 12. “You just say to yourself, You can’t fall apart,” Neeson says. “

And you just can’t. You’re responsible for two lives. Of course, it’s a tragedy, and life throws awful curveballs at you sometimes, but you have to cope.” He gained strength, he says, from his family and from Richardson’s, including her mother, actress Vanessa Redgrave, with whom he’s very close.

“You could ask them to do anything, and it would be done,” he says. “They stopped their lives to look after us. I was very, very lucky.”

The epitaph on Richardson’s tombstone is “Cast your bread upon the water, and it will be returned tenfold.” Neeson is, by the account of his friends, extraordinarily generous.

Aidan Quinn says he has made large contributions to the school that Quinn’s daughter, who is autistic, attended. When Maggie Grace made her Broadway debut in Picnic in 2013, Neeson was there. It was the same theater where Neeson and Richardson had performed.

If it was painful for him, he didn’t show it. “He came backstage, and everyone was so excited to see him,” Grace says. “He still remembered funny stories and the names of the folks who had been there when he and Natasha were in Anna Christie.”

Jules Daly, who was the producer on two of Neeson’s films—The Grey and The A-Team—sums up his appeal. “Liam’s like the last man on earth,” she says. “He’s chivalrous, but he’s a great supporter of women. He’s got your back. This is a man who looks you in the eye when he asks you how you are.

He really, truly cares. He remembers things about your family, he wants to see pictures of your kids, and he remembers the names of everyone on the crew, down to the grips. Liam defines authentic.”