The “all or nothing” armor scheme revolutionized battleship design in the early 20th century by concentrating armor around the most vital areas, such as ammunition magazines and propulsion systems, while leaving less critical areas less protected.

This approach significantly enhanced battleship survivability in combat, enabling these ships to sustain damage yet continue fighting effectively.

Adopted first by the United States Navy with the Nevada-class battleships, the “all or nothing” concept influenced naval architecture worldwide, setting new standards for naval engineering and tactics in the era of dreadnought battleships.

The origins of the “all or nothing” armor concept in battleship design can be traced back to the early 20th century, a period marked by rapid technological advancements in naval artillery and armor.

Prior to this era, battleship design followed a principle of distributed armor, which entailed spreading armor over as much of the ship’s surface as possible.

This strategy aimed to provide a baseline level of protection against gunfire and explosive shells, with armor plates covering not just the vital areas but also less critical sections of the ship.

However, as naval guns grew more powerful and their range increased, the effectiveness of distributed armor began to wane.

It became increasingly clear that thin armor spread across a large area could not provide sufficient protection against the heavy shells of enemy battleships.

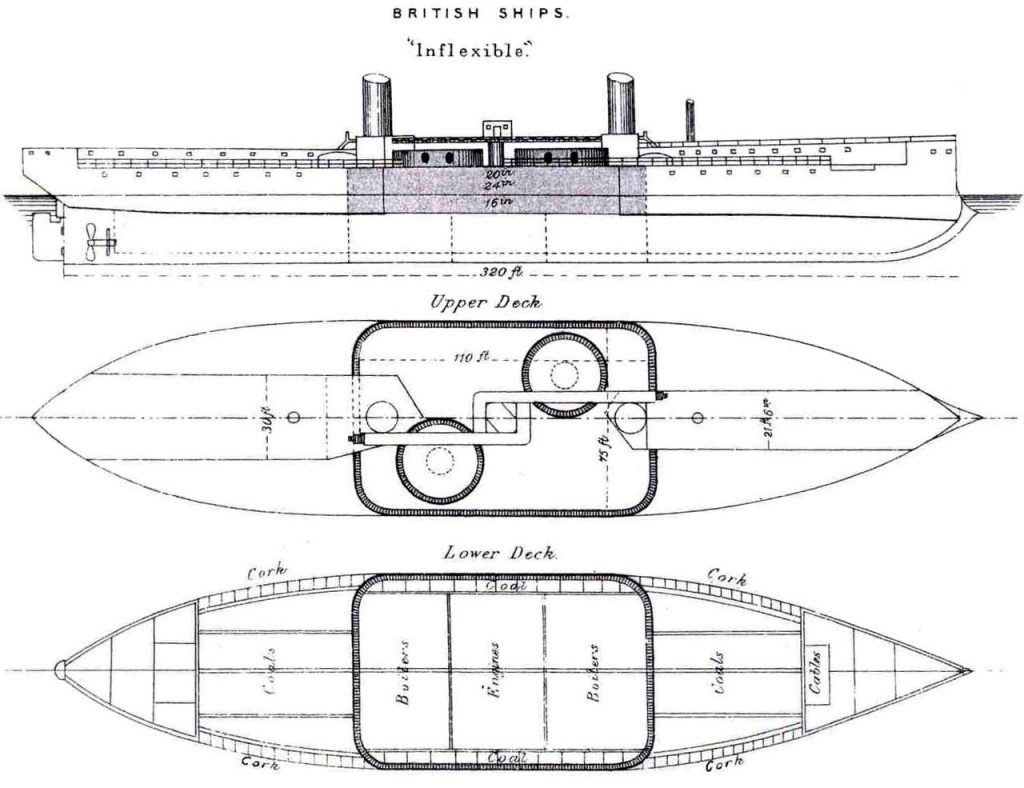

HMS Inflexible was an ironclad ship that featured an armored citadel with lesser armored ends.

HMS Inflexible was an ironclad ship that featured an armored citadel with lesser armored ends.

The advent of “all or nothing” armor was a direct response to these challenges. The realization that it was impractical to protect every part of a ship equally against powerful modern artillery led naval architects to a new philosophy.

Instead of attempting to shield the entire ship, the focus shifted to concentrating armor on the most critical areas—those whose damage or destruction would most likely lead to the loss of the ship.

These included the magazine areas, where ammunition was stored, and the machinery spaces, which housed the engines and propulsion systems.

Protecting these key areas meant that a ship could remain operational and continue fighting even after taking significant hits elsewhere.

The United States Navy’s adoption of the “all or nothing” concept was influenced by several key figures, including naval officers and designers who recognized the need for a more effective approach to battleship armor.

Early Implementations

The Nevada-class battleships, including USS Nevada (BB-36) and USS Oklahoma (BB-37), launched in 1914, were the first to feature the “all or nothing” armor scheme comprehensively.

These ships were designed with several key characteristics that embodied the principles of the “all or nothing” concept:

Centralized Protection: The most significant aspect of the “all or nothing” design was the concentration of thick armor in the central part of the ship, covering the magazines and machinery spaces. This heavy armor belt extended vertically from the keel to well above the waterline, ensuring protection against underwater threats and direct hits.

Armored Citadel: The protected area formed an armored citadel, with transverse bulkheads at the fore and aft connecting to the main belt, creating a box of armor that enclosed the most vital components. This ensured that critical areas were shielded from direct fire and splinters.

Deck Armor: Recognizing the threat of plunging fire at long ranges, the design included thick armored decks over the citadel. This deck armor was critical in defending against shells that descended at steep angles, penetrating the ship from above.

USS Nevada was the first ship to incorprate all or nothing armor.

USS Nevada was the first ship to incorprate all or nothing armor.

Turret and Barbettes Armor: The gun turrets and their supporting barbettes (the armored cylinders that housed the turret’s lifting mechanisms) received substantial armor.

This was essential to maintain the ship’s offensive capabilities even under heavy fire.

Conning Tower Protection: The conning tower, from where the ship was commanded during battle, was heavily armored to protect the ship’s leadership and maintain command and control.

The adoption of the “all or nothing” scheme involved strategic trade-offs. Areas deemed non-essential for the ship’s survival in combat, such as the bow and stern sections and the superstructure, received minimal armor.

This decision was rooted in the understanding that while such areas could be damaged or destroyed, the ship could still remain operational and effective in battle as long as the armored citadel was intact.

The implementation of the “all or nothing” armor scheme influenced not just the Nevada-class but subsequent battleship designs, both in the United States and internationally.

Naval architects recognized the value of concentrating armor to maximize protection without excessively increasing displacement.

This approach allowed for greater freedom in ship design, enabling the inclusion of larger guns and more powerful engines within the constraints of treaty limits on displacement and armament.

Impact of All or Nothing Armor

The primary impact of the “all or nothing” armor scheme was on the survivability of battleships in naval combat.

By concentrating armor around the most vital areas of the ship, such as the ammunition magazines and propulsion systems, battleships could withstand significant damage and continue fighting.

This was a critical advantage in naval engagements, where the ability to sustain combat effectiveness after taking hits was often the difference between victory and defeat.

Battleships equipped with “all or nothing” armor proved to be more resilient against both direct hits and underwater explosions, such as torpedoes, which were becoming increasingly common threats.

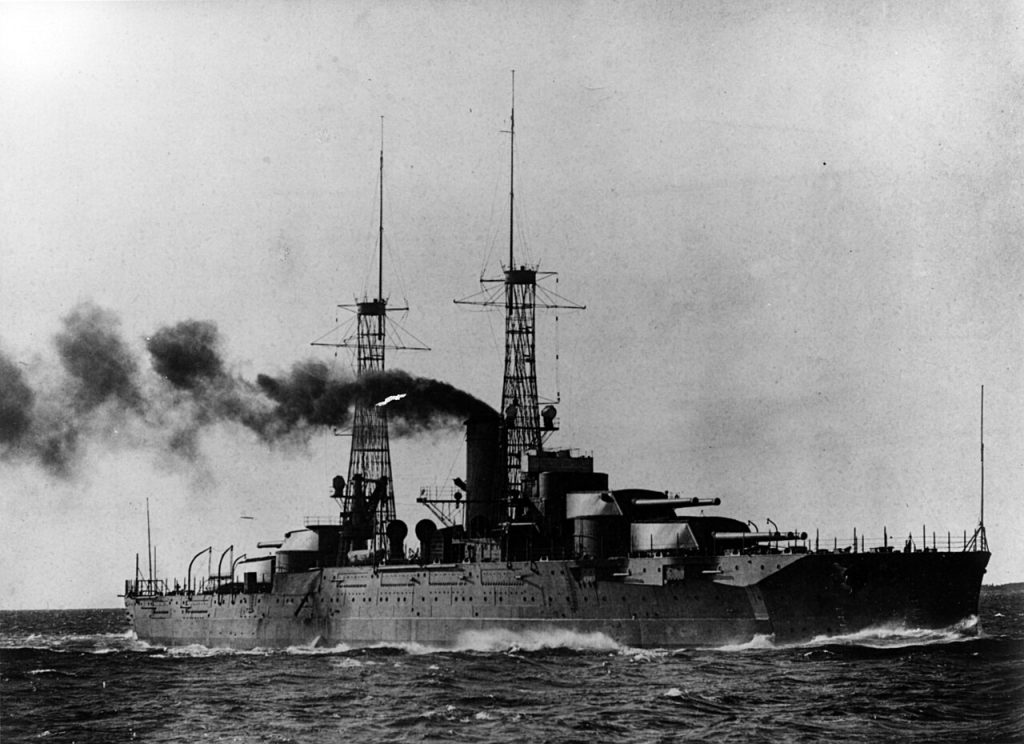

The effectiveness of the “all or nothing” armor scheme influenced naval strategies around the world.

Navies that observed the performance of ships with this type of armor began to incorporate similar designs into their own battleships and other capital ships.

The Iowa-class battleship USS New Jersey was built with all or nothing armor. Here is a good example showing the hatch and citadel armor which was 17 inches thick.

The Iowa-class battleship USS New Jersey was built with all or nothing armor. Here is a good example showing the hatch and citadel armor which was 17 inches thick.

This led to a shift in naval tactics, with a greater emphasis placed on long-range engagements where the concentration of armor could be most effectively exploited.

It also affected the development of naval artillery, as navies sought to develop guns capable of penetrating heavily armored citadels at great distances.

The implementation of the “all or nothing” scheme necessitated changes in shipbuilding practices.

Designers and engineers had to develop new methods for integrating heavy armor into the structure of battleships without compromising their seaworthiness or maneuverability.

This led to innovations in steel manufacturing and hull design, allowing for the production of stronger, more resilient armor plates and more efficient ship layouts.

The challenge of balancing armor protection with other design priorities, such as speed and armament, drove advancements in naval engineering and architecture.

The real-world performance of battleships with “all or nothing” armor in major naval engagements, such as the Battle of Jutland during World War I, provided valuable lessons in the effectiveness of the concept.

These battles demonstrated that ships with concentrated armor were better able to survive and continue fighting, even after sustaining multiple hits.

The analysis of battle damage and the operational history of these ships contributed to further refinements in armor design and tactics, shaping future generations of naval vessels.