Of all the many known aircraft wrecks in the Pacific, the B-17 “Swamp Ghost” on Papua New Guinea is probably the most famous.

This bomber was lost in early 1942 while returning home from the United States’ first strategic bombing mission of the Second World War, crash landing into a swamp with the survival of all on board.

Leaving the aircraft, they faced a six week fight with swamps and jungle, before finally being evacuated. The B-17 was “rediscovered” in the 1970s and found in perfect condition, still outfitted with its machine guns, ammunition, electronics, engines etc.

Over three decades later, the bomber was controversially removed by a salvager and saved.

How it Ended Up in a Swamp

The B-17 “Swamp Ghost” of course, did not always have that name. It was a B-17E, one of the earliest B-17 models used during the war, and the first used without the earlier “shark fin” tail.

She was built in Boeing’s factory in Seattle, Washington on November 28, 1941 – just 9 days before the Attack on Pearl Harbour – and accepted into the US Army Air Force in December with the serial number 41-2446.

After bouncing around a few airfields in the US, Swamp Ghost was assigned to a squadron. At this point she was paired with her 25-year old captain, Frederick C. Eaton, Jr. as part of the 7th Bomb Group, 22nd Bomb Squadron.

Frederick C. Eaton, Jr.

Frederick C. Eaton, Jr.

Swamp Ghost then relocated to Hawaii and flew anti-submarine missions for the next few months while temporarily assigned to the US Navy.

This continued until February 1942, when she began a long island-hopping journey across the Pacific to Townsville in Queensland, Australia, 7,500 km (4,700 miles) away.

This was the opening days of the Pacific Campaign, and she was one of only nine B-17s in Australia at the time. Because of this the bombers lacked the proper mechanics on the ground, so the B-17 crews had to load and prepare their aircraft themselves.

Garbutt Field (RAAF Townsville) was one of the busiest airfields in Australia at its peak.

Garbutt Field (RAAF Townsville) was one of the busiest airfields in Australia at its peak.

Within days of her arrival, Swamp Ghost and the other eight B-17s were assigned their first bombing mission against the enemy. The target was Japanese shipping in Simpson Harbor, 1,700 km (1,100 miles) away in Rabaul near Papua New Guinea.

This was an extremely long round trip, so the B-17s were to stop off in Port Moresby to refuel on their way back to Australia. They also weren’t going to be escorted.

The aircraft fired up their engines to depart on the evening of February 22, 1942, but the mission immediately got off to a bad start. Two aircraft collided while taxiing, and a third faced mechanical issues with its number 3 engine before it took off.

B-17E 41-2416, one of the aircraft involved in the collision.

B-17E 41-2416, one of the aircraft involved in the collision.

The remaining six took off as planned, and headed for the target in Rabaul. The B-17s ran into poor weather on the way, and one turned back. The rest arrived individually and made runs against the target.

Swamp Ghost’s first run was unsuccessful – often attributed to a mechanical issue with the bomb bay doors that prevented them from opening. Others say bad weather obscured the target on the first run.

Regardless, they made a second attempt and dropped their bombs on a Japanese ship in the harbor, although they weren’t able to establish if they hit or not. But on this second attempt the aircraft’s right wing was punctured by a Japanese anti-aircraft round that failed to explode.

Simpson Harbor was extremely important to the Japanese, and was attacked numerous times.

Simpson Harbor was extremely important to the Japanese, and was attacked numerous times.

Swamp Ghost then made a hasty retreat home but was harassed and damaged by Japanese fighters. Her crew slammed the throttles forward and gained altitude to loose the fighters, and the tough airframe of the B-17 was able to carry on flying despite being hit by cannon fire.

However, pushing the engines so hard used lots of fuel.

As the aircraft approached the northern coast of Papua New Guinea she was almost empty, and still needed to travel over the Owen Stanley Mountain Range that sat between them and their stop-off in Port Moresby.

Captain Eaton knew they weren’t going to make it, so he decided to bring the aircraft down in a wheels-up landing, having spotted a nice and level wheat field.

At least that is what they thought it was, as they quickly found that they had actually landed in a large swamp.

It was the Agaiambo Swamp, a few miles across and infested with razor-sharp kunai grass and mosquitos just behind Papua New Guinea’s northern coast.

The good news was that the pilots landed her perfectly and incurred essentially no damage to the airframe, allowing all nine crew members to step out unscathed.

The bombardier destroyed the top-secret Norden bomb sight by shooting it with his .45 and chucking it into the swamp.

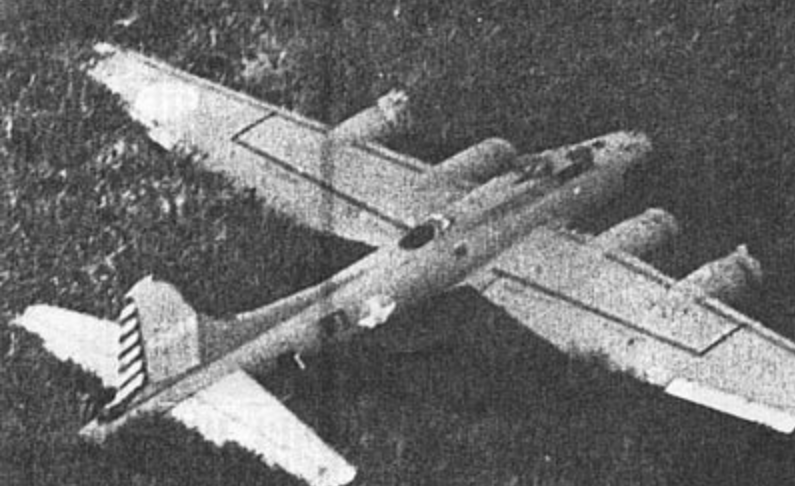

Swamp Ghost a few months after she landed. This image shows how she skidded along and spun to the right during her landing.

Swamp Ghost a few months after she landed. This image shows how she skidded along and spun to the right during her landing.

For the next two days the crew chopped and trudged their through the waist-height swamp, being cut by the grass and attacked by mosquitos as they went.

To begin with they brought their equipment, pulling it along in one of the B-17’s life rafts, but they soon abandoned this plan as it was simply to exhausting.

They tried to rest at night by sleeping on mounds, but these would only sink into the swamp.

Eventually making it out of the swamp, the men were exhausted, riddled with mosquito bites and some had contracted malaria.

In this closer shot of Swamp Ghost taken by the USAAF, its markings are clearly visible, including the red and white striped rudder.

In this closer shot of Swamp Ghost taken by the USAAF, its markings are clearly visible, including the red and white striped rudder.

Fortunately they encountered a local Papuan who took them into a nearby village. The villagers made contact with an Australian magistrate, who helped organise their extraction from Papua New Guinea.

36 days after landing in the swamp, Swamp Ghost’s crew reached the safety of Port Moresby by boat. The crew spent a short stint recovering from the ordeal and hospital in Australia, before returning to duty.

Swamp Ghost’s Wreck

It was not possible to recover Swamp Ghost, so the aircraft was written off and left in place. The B-17 then became a well-known landmark among American airmen, who would sometimes fly over it on the way back from missions in the area.

Even Captain Eaton stared back down at his former aircraft a few times.

Swamp Ghost was periodically seen by fliers overhead. It was almost entirely hidden in the wet season by grass.

Swamp Ghost was periodically seen by fliers overhead. It was almost entirely hidden in the wet season by grass.

Many sources state that the wreck was forgotten about after the war, however some familiar many in the area knew of its existence before its official discovery. Outside of this it wasn’t known, however, and its position within the swamp managed to keep visitors away.

Discovering Swamp Ghost

A local patrol officer had seen the B-17 from above a number of times, and in 1972 asked an Australian Army unit, who were on exercises in the area, to take him to the site on one of their Iroquois helicopters.

The helicopter perched gently on the wing, dropping off the patrol officer and a handful of army personnel before departing.

A view into the nose of Swamp Ghost. This image was taken after the aircraft was moved to the US – when it was found it was in much better condition. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

A view into the nose of Swamp Ghost. This image was taken after the aircraft was moved to the US – when it was found it was in much better condition. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

The tail gunner position was submerged, but the rest of the aircraft was accessible. Upon entering the fuselage, they were stunned to find that it hadn’t been touched since the war, and was an incredibly well-preserved time capsule.

Despite years in the swamp, it remained as it was when the last crewmember climbed out of it three decades earlier. The .50 caliber machine guns were all still present, as were large quantities of their ammunition. Instrumentation, wiring, seats, paintwork, markings, engines and more were all in intact.

Incredibly, as this was an early B-17, much of the equipment installed inside actually predated the war, being made in the 1930s.

Swamp Ghost after recovery and transportation to Hawaii. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

Swamp Ghost after recovery and transportation to Hawaii. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

The patrol officer entered the nose section and found a pair of .50 caliber machine guns stored above the long-vacant radio operator’s desk, along with belts upon belts of ammunition. As they had been kept within the aircraft, they were in exceptional condition.

He removed them from the aircraft for preservation and took them back with him. He donated one to a local district office, and kept the other one with him. In the 1990s he would be get into legal trouble with the Australian government over possession of this firearm.

To avoid the authorities destroying the weapon, he arranged its donation to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Australia where it remains today.

Curiously, the fate of the other machine guns has not been established.

Swamp Ghost would rise to world-fame in 1979, when an aircraft collector published detailed images of it in the book Pacific Aircraft Wrecks. Naturally, this drew large numbers of visitors to the bomber, who sadly stripped it of items.

The aircraft was also given the name “Swamp Ghost” by the media.

Recovery

In the 1980s there were attempt to salvage the wreckage, with one coming from the Travis Air Force Museum, who offered to exchange the wreck for several restored aircraft delivered to the Papua New Guinea Museum.

In the 1990s Alfred Hagen came onto the scene, purchasing the rights to the wreck from another interested party.

Many of the aircraft’s original markings are still visible. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

Many of the aircraft’s original markings are still visible. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

He entered into a difficult and controversial battle with the Papua New Guinea to obtain permission to recover the wreck that would last until 2006. By that point the aircraft had now begun to deteriorate and was being destroyed piece-by-piece by souvenir hunters.

In that year Hagen started salvaging the aircraft. A multinational crew separated the wings, engines and tail, lifting each section out of the swamp with an Mi-8 helicopter.

The salvage work raised the bottom of the fuselage out of the swamp, allowing the crews to access and remove the two .50 caliber machine guns in the belly turret.

The helicopter flew the parts to a barge on the coast, which then transported them to city of Lae. However by this point the salvage had become national news, and there were large protests by the locals.

Swamp Ghost was divided up into parts and transported out of the swamp. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

Swamp Ghost was divided up into parts and transported out of the swamp. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

Some viewed the operation as morally wrong, while others were angered because the removal of the aircraft would impact them financially, as it created a local tourist industry.

On the other hand, those who wanted to raise the aircraft had their own financial incentives, but also believed that this historical time capsule must be saved before it was destroyed.

That year a Papua New Guinea committee investigated Hagan’s salvage and found it to be illegal. But after years of negotiations, Hagen made a deal with Papua New Guinea and was allowed to transport the bomber back to the United States in 2010. The situation is still regarded as controversial today.

The incredibly well-preserved frontal nose section of Swamp Ghost. Sadly, souvenier hunters removed most of the aircraft’s internal fittings. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

The incredibly well-preserved frontal nose section of Swamp Ghost. Sadly, souvenier hunters removed most of the aircraft’s internal fittings. Image by Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum CC BY 2.0.

It was located in California for a while, but in 2013 it was moved to the Pacific Aviation Museum on Hawaii, where its career in the Pacific began.

The salvage of this aircraft was controversial, and remains so to this day. However, if this didn’t occur and the bomber was left to a nation with lesser resources and interest for such a project, Swamp Ghost may have met the same fate as Lady Be Good, or the P-40 Kittyhawk found in the Sahara in 2012.