The Battle of the River Plate, fought in December 1939, was the first significant naval battle of World War II between Britain and Germany.

A British hunting group consisting of three cruisers—HMS Exeter, HMS Ajax, and HMNZS Achilles—confronted the formidable German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee off the coast of Uruguay.

After a fierce engagement, the damaged Graf Spee sought refuge in the neutral port of Montevideo and was eventually scuttled by its crew, marking a strategic victory for the Allies.

Admiral Graf Spee’s Reign Of Terror

In the early days of World War II, the waters of the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans became an ominous backdrop for a deadly game of cat and mouse.

The central figure in this maritime drama was the Admiral Graf Spee, one of Nazi Germany’s formidable Deutschland-class “pocket battleships.”

This vessel was uniquely positioned to play a disruptive role in the vast expanses of the oceans due to its blend of firepower, speed, and extended operational range.

Before diving into the Graf Spee’s actions, it’s crucial to understand its design. The term “pocket battleship” might sound diminutive, but it was a term of classification rather than a comment on its potency.

These ships were constructed to meet the stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles, which imposed restrictions on the size and armaments of German naval vessels.

To circumvent these limitations, the Germans ingeniously designed the Deutschland-class vessels. They were smaller and lighter than traditional battleships but carried disproportionately large guns for their size, making them a significant threat to enemy vessels, especially merchant ships.

Equipped with six 11-inch guns, eight 5.9-inch secondary guns, and an array of smaller anti-aircraft and anti-ship weapons, the Graf Spee could quickly engage and destroy most opponents it encountered.

Its diesel engines granted it a cruising range of around 16,000 nautical miles at 19 knots, allowing it to remain at sea for extended periods, making it harder for the Allies to predict its next move.

The Admiral Graf Spee shortly after its commissioning in 1936.

The Admiral Graf Spee shortly after its commissioning in 1936.

Under the command of Captain Hans Langsdorff, a seasoned and astute naval officer, the Graf Spee was unleashed upon the Allied merchant shipping lanes.

Between September and December 1939, this pocket battleship became a veritable nightmare for the Allies, sinking nine merchant ships totaling over 50,000 gross register tons.

But Langsdorff’s strategy was not one of indiscriminate destruction. He often ensured the safety of the crews of the ships he targeted.

Prisoners were treated with respect, and in many cases, they were set adrift in lifeboats or taken aboard the Graf Spee to be later released.

Langsdorff’s chivalrous behavior became well-known and was a stark contrast to the brutal nature of warfare elsewhere.

The British Royal Navy, recognizing the magnitude of the threat posed by the Graf Spee, began efforts to track and neutralize it. Given the vastness of the operational area, this was no easy task.

To address this, the British Admiralty formed hunting groups, coalitions of ships with the express purpose of locating and engaging the Graf Spee.

The stage was set for a confrontation that would become one of the most dramatic naval engagements of the early war period.

The Battle Of River Plate

The expansive waters of the South Atlantic, near the estuary of the River Plate, became the unlikely arena for a fierce naval showdown in December 1939.

On the morning of December 13, the British hunting group, comprising of three cruisers – HMS Exeter, HMS Ajax, and HMNZS Achilles (the last being from the New Zealand Division) – made contact with the Graf Spee.

Led by Commodore Henry Harwood, these ships, while individually less powerful than the German pocket battleship, relied on their numbers and agility.

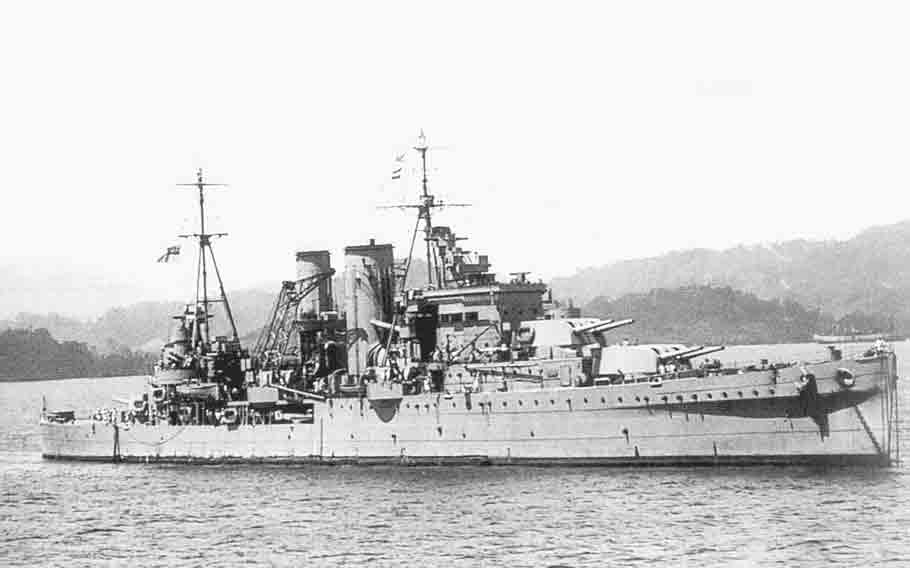

HMS Exeter pictured in 1942.

HMS Exeter pictured in 1942.

The confrontation started with the Graf Spee opening fire on the HMS Exeter, as Captain Hans Langsdorff seemed to believe that neutralizing the biggest threat first would grant him an advantage.

The Exeter, being a heavy cruiser with six 8-inch guns, was indeed a significant adversary.

As the shells splashed and boomed, the Exeter took a heavy beating, with its superstructure damaged, several guns knocked out, and fires raging on deck.

While the Graf Spee focused much of its firepower on the Exeter, the other two cruisers, Ajax and Achilles, adeptly moved into action.

Using their speed and smaller profile, they began a series of rapid maneuvers, darting in and out of range, drawing fire, and launching salvoes whenever opportunities presented.

Their goal was twofold: to split the Graf Spee’s attention, making it harder for her to concentrate fire, and to create openings for the Exeter to retaliate.

Commodore Harwood’s tactics aimed at keeping the Graf Spee engaged. The longer the battle raged, the better the chances that reinforcements could arrive or that the Graf Spee might make a mistake.

Moreover, the British cruisers often laid down smoke screens during the battle.

These screens served dual purposes: they obscured the British ships from the Graf Spee’s gunners, and they also created an illusion of additional ships joining the fray, adding to Langsdorff’s uncertainty.

For several hours, this high-stakes dance of shells, smoke, and strategy played out on the waters of the South Atlantic. Despite the initial onslaught, the Exeter, though heavily damaged, continued to engage.

Its resilience, combined with the constant harassment from the Ajax and Achilles, began to wear on the Graf Spee.

The cruiser HMS Achilles seen from HMS Ajax during the Battle of the River Plate.

Captain Langsdorff faced a dilemma. While his ship had sustained damage, especially to its fuel processing systems, it was still a potent force. However, continuing the battle presented risks.

His ammunition was depleting, and the potential for more British ships to join the fight was a looming threat.

In a surprising twist, Langsdorff chose a strategic retreat. Instead of seeking to finish off the damaged Exeter or attempting to destroy the Ajax and Achilles, he steered the Graf Spee towards the neutral port of Montevideo in Uruguay.

This move marked the end of the direct confrontation but set the stage for an even more intense psychological and diplomatic showdown in the days that followed.

The Surprise Decision

The heat of battle is a crucible where decisions can reshape the course of events in unforeseen ways.

Captain Hans Langsdorff’s decision to steer the Admiral Graf Spee towards Montevideo in the aftermath of the confrontation at the River Plate was such a moment—a choice wrapped in layers of strategy, human considerations, and external pressures.

Captain Langsdorff, by the end of the direct confrontation with the British hunting group, found himself in a precarious situation.

Although the Graf Spee had inflicted significant damage on the HMS Exeter and engaged with HMS Ajax and HMNZS Achilles, it was not unscathed.

The damage to the ship’s fuel processing system hindered its ability to operate at peak performance, and the constant engagement had depleted its ammunition reserves.

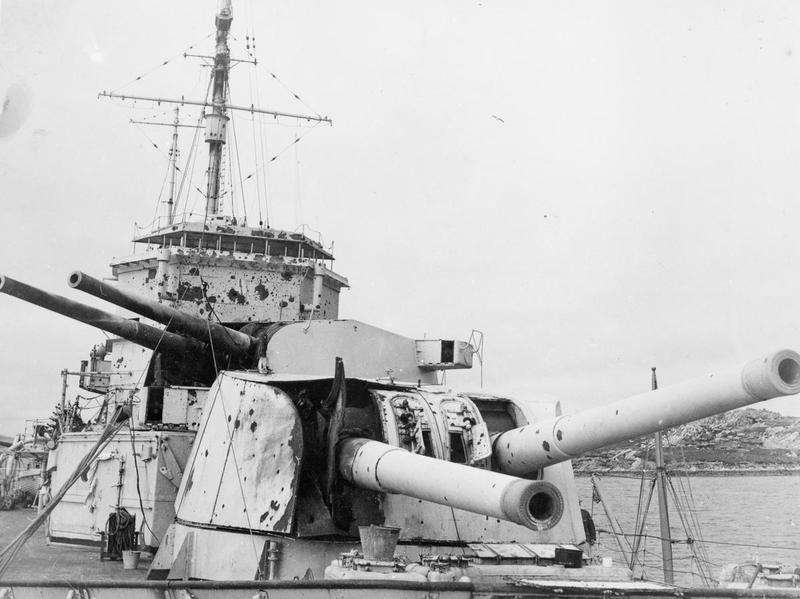

The wounds recieved by HMS Exeter during the battle.

The wounds recieved by HMS Exeter during the battle.

A prolonged engagement presented risks. The Graf Spee’s status as a commerce raider depended on its ability to remain elusive, picking off merchant ships while avoiding significant confrontations with larger naval fleets.

A continued battle with the British cruisers, especially with the threat of potential reinforcements, could jeopardize the ship’s core mission and the lives of its crew.

International maritime laws provided some protections for warships in neutral ports. A belligerent ship could seek refuge, perform repairs, and tend to its wounded.

However, these laws also imposed restrictions. A combatant vessel could only remain in a neutral port for a limited time, after which it had to depart or be interned by the neutral country for the duration of the war.

By heading to Montevideo, Langsdorff hoped to buy time. This decision provided a temporary reprieve, allowing the crew to address the ship’s most pressing damages and care for the injured.

Yet, it also trapped the Graf Spee in a diplomatic quagmire, with the clock ticking on its mandated departure.

The British, recognizing the unique opportunity presented by the Graf Spee’s decision to dock in Montevideo, initiated a campaign of misinformation and psychological warfare.

Using covert networks, rumors were spread about significant British reinforcements converging on the River Plate, poised to engage the Graf Spee should it leave the safety of the harbor.

These rumors played on the very real concerns of Captain Langsdorff. The idea of facing a superior British force, especially when the Graf Spee was not at its full operational capacity, must have weighed heavily on his mind.

Faced with mounting pressures, both real and perceived, Captain Langsdorff was at a crossroads. Engaging a potentially larger British fleet was a daunting prospect.

Remaining in Montevideo indefinitely wasn’t an option due to international law. This left Langsdorff with few viable choices.

On December 17, Langsdorff made the fateful decision to scuttle the Admiral Graf Spee. This act ensured that the ship would not fall into enemy hands.

The Admiral Graf Spee burns shortly after she was scuttled.

The Admiral Graf Spee burns shortly after she was scuttled.

The scuttling of a potent naval vessel in such circumstances was unprecedented.

Aftermath

Following the scuttling, the crew of the Admiral Graf Spee was interned in Argentina.

Argentina, being a neutral country, was obligated by international law to intern belligerent military personnel for the duration of hostilities to prevent their return to the conflict.

Most of the crew remained interned until 1945, after which they were repatriated to Germany.

Hans Langsdorff and the crew of the Admiral Graf Spee at the burial of the German sailors.

Hans Langsdorff and the crew of the Admiral Graf Spee at the burial of the German sailors.

A few days after the decision to scuttle his ship, Captain Hans Langsdorff took responsibility for his actions to protect the honor of his crew and the German navy.

In a Buenos Aires hotel room, he laid on the flag of the Imperial German Navy and took his own life.

His final letters expressed that he believed his actions were in the best interest of his crew and the honor of the navy, but he felt the weight of the situation profoundly.

The inability of the Graf Spee to break out of Montevideo and its subsequent scuttling was celebrated as a significant victory by the Allies.

Even though the Royal Navy’s force had been substantially outgunned, their tactics and psychological warfare played a decisive role in cornering the formidable German pocket battleship.

The outcome bolstered the morale of the Allied nations at a crucial early stage in the war.

Who sank the Graf Spee?

The British Navy sank the Graf Spee during World War 2 with help from several allied nations. The Graf Spee was more than 600 feet long and had 1150 crew members and many artillery weapons.

When World War 2 started, the Graf Spee patrolled the Atlantic, sinking eight merchant ships.