The German battleship Bismarck, one of the most formidable naval warships of World War II, embarked on its maiden voyage in May 1941 under Operation Rheinübung with the mission to disrupt Allied shipping lanes in the Atlantic.

After sinking the British battlecruiser HMS Hood in the Battle of the Denmark Strait, the Bismarck was relentlessly pursued by a vengeful British Royal Navy, culminating in a decisive confrontation where it was incapacitated by a torpedo strike to its rudder.

Finally, on May 27, 1941, after a fierce and prolonged battle involving numerous British naval vessels, the Bismarck was sunk, marking a significant British naval victory and a crucial moment in the Battle of the Atlantic.

The Bismarck

The German battleship Bismarck, launched on February 14, 1939, was a masterpiece of naval engineering and a symbol of the Third Reich’s military ambitions.

As part of Hitler’s plan to rebuild Germany’s naval forces under the Kriegsmarine, Bismarck was designed to project power and assert German dominance over the seas.

With a displacement of over 50,000 tons and an overall length of 251 meters, the Bismarck was not only immense but also crafted to balance firepower, armor, and speed.

The Bismarck’s design was a culmination of German naval innovation and strategic military planning. It featured an array of armaments that made it a formidable opponent in naval warfare.

The main battery consisted of eight 15-inch (380 mm) guns housed in four twin turrets, capable of firing shells that weighed up to 800 kg over a range exceeding 36 kilometers.

This powerful artillery was complemented by twelve 5.9-inch guns, sixteen 4.1-inch guns, and an array of anti-aircraft guns that enhanced its defensive capabilities against aerial attacks.

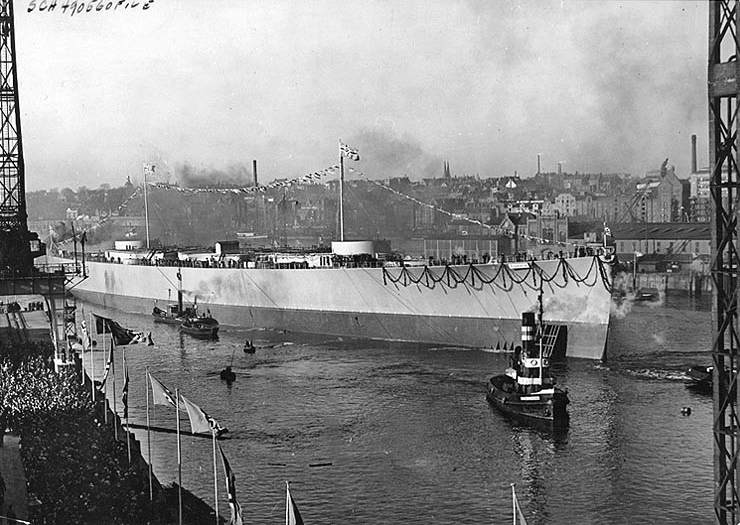

The Bismarck after launching, 14 February 1939.

The Bismarck after launching, 14 February 1939.

The ship’s armor was equally impressive, with a main belt of up to 320 mm of steel and a double bottom that spanned almost the entire length of the hull.

The design also included a sophisticated compartmentalization system intended to enhance survivability in the event of breaches from torpedoes or shellfire.

Bismarck’s propulsion system was state-of-the-art, featuring three steam turbines and twelve boilers, which generated a staggering 150,000 shaft horsepower.

This power plant enabled the battleship to reach speeds of up to 30 knots, making it one of the fastest battleships of its era.

Such speed allowed Bismarck to outrun many of the ships that could outgun it and to outgun any ship that could outrun it, a crucial advantage in naval engagements.

Furthermore, the Bismarck was equipped with the latest naval technology, including radar detection systems that provided critical intelligence on enemy movements and positioning.

This technological edge was complemented by substantial operational range, capable of conducting long-duration missions without the immediate need for refueling or resupply.

The battleship pictured in 1940.

The battleship pictured in 1940.

The mere presence of Bismarck in the Atlantic was a significant psychological threat to the Allies.

It challenged the naval supremacy of the British Empire and represented a direct threat to the Atlantic convoys that were vital for the sustenance of Britain’s war effort.

The Bismarck’s intended role in disrupting these supply lines made it a prime target for the British navy, which would go to extraordinary lengths to ensure that the battleship’s first mission would also be its last.

The Bismarck Enters the Foray

Operation Rheinübung marked the Bismarck’s debut into the theater of World War II, a mission that was both ambitious and perilous.

The operation, initiated in May 1941, involved the Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, and it was intended to disrupt Allied shipping routes between North America and Great Britain, which were crucial for supplying Britain with the necessary resources to continue the war effort.

The Bismarck pictured from the deck of the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, 21 May 1941.

The Bismarck pictured from the deck of the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, 21 May 1941.

The primary objective of Operation Rheinübung was to break into the North Atlantic and wreak havoc on Allied shipping lanes.

By doing so, the Kriegsmarine aimed to draw out and tie down British naval forces, reduce the flow of supplies to Britain, and thereby weaken Britain’s capacity to sustain the war.

This kind of raiding mission was typical of German surface fleet operations, which preferred engaging enemy merchant shipping rather than directly confronting the larger Royal Navy fleets.

Under the command of Admiral Günther Lütjens, the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen left the port of Gotenhafen (now Gdynia, Poland) and headed towards the Denmark Strait, which separates Greenland from Iceland.

This route was chosen because it was less heavily patrolled than other potential paths and offered a higher chance of breaking through into the open Atlantic undetected.

However, the plan quickly encountered complications. British intelligence, aided by decrypted German naval signals, became aware of the operation.

The Royal Navy mobilized a significant force, including the battlecruiser HMS Hood and the new battleship HMS Prince of Wales, to intercept the German squadron.

The British intended not only to protect vital Atlantic convoys but also to eliminate the threat posed by the Bismarck and its escort.

As Bismarck and Prinz Eugen navigated through the Denmark Strait on May 24, 1941, they were spotted by the British cruisers HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk.

These cruisers began shadowing the German ships, maintaining contact and guiding the main British fleet towards them.

The ensuing confrontation in the Denmark Strait led to one of the most dramatic naval battles of the war.

The Bismarck shortly after the Battle of the Denmark Strait.

The Bismarck shortly after the Battle of the Denmark Strait.

During the battle, Bismarck’s superior firepower and robust armor were clearly demonstrated when it engaged and sank the HMS Hood, the pride of the Royal Navy, with a devastating salvo that detonated the Hood’s magazine, causing the ship to blow up and sink within minutes.

The loss of the Hood, with 1,418 crew members, was a profound shock to the British public and the Royal Navy but also intensified their resolve to destroy the Bismarck.

Despite the success in sinking the Hood, the Bismarck did not emerge unscathed.

It suffered a fuel tank leak from a hit taken during the engagement, which limited its operational range and forced Admiral Lütjens to consider returning to port for repairs.

This decision set the stage for the intense chase and subsequent engagements that would eventually lead to the demise of the Bismarck.

The Hunt Begins

The hunt began in earnest after the Bismarck’s successful engagement with HMS Hood and HMS Prince of Wales.

Despite the sinking of the Hood, the Prince of Wales managed to score hits on Bismarck, causing damage that would prove critical later.

Following the battle, the Bismarck attempted a strategic retreat to occupied France for repairs, using inclement weather to mask its escape.

However, the British were determined not to let the battleship slip away.

The Bismarck firing during The Battle of the Denmark Strait.

The Bismarck firing during The Battle of the Denmark Strait.

British naval units, including cruisers HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk, continued to shadow Bismarck through the Denmark Strait.

These ships were crucial in maintaining contact with the Bismarck, using their radar capabilities to track the German battleship despite adverse weather conditions and the fall of night.

As Bismarck entered the open Atlantic, the British Admiralty mobilized an unprecedented force to track and engage it.

This included not just the remaining units of the Home Fleet, but also forces pulled from escort duties and even convoys.

Aircraft from Coastal Command and the carrier HMS Victorious were deployed in the hope of locating and slowing down the German ship.

The British were fully aware that if Bismarck managed to break into the Atlantic, it could devastate the vital convoys supplying Britain from North America.

On the evening of May 24, aircraft from HMS Victorious managed to score a hit on Bismarck with a torpedo, though it did little to slow the ship.

This attack, however, confirmed Bismarck’s location and helped the Royal Navy to coordinate their efforts.

The pursuit of the Bismarck not only involved direct naval engagement but also the sophisticated use of intelligence and technology.

British codebreakers at Bletchley Park played a vital role by intercepting and decrypting German naval communications, which helped clarify Bismarck’s intentions and potential course.

This intelligence allowed the Royal Navy to anticipate Bismarck’s movements and strategically position their naval forces.

Furthermore, advancements in radar technology proved instrumental during the hunt.

British ships equipped with radar had a significant advantage in terms of night-time and foul-weather operations, allowing them to maintain contact with Bismarck even under challenging conditions.

This technological edge was crucial in the effective coordination and execution of the Royal Navy’s strategy.

Ultimately, the continuous pressure from the Royal Navy, combined with the significant damage Bismarck sustained, slowed its progress, making it vulnerable to further attacks.

The final confrontation was precipitated by an aircraft sighting by a Catalina flying boat on May 26, which corrected previous assumptions about Bismarck’s course and led to a decisive air attack from the carrier HMS Ark Royal.

The torpedo planes from Ark Royal delivered the crippling blow by damaging Bismarck’s rudder, rendering it almost unmaneuverable.

A Fairey Swordfish returning to HMS Ark Royal after attacking the Bismarck with a torpedo.

A Fairey Swordfish returning to HMS Ark Royal after attacking the Bismarck with a torpedo.

The Demise of the Bismarck

After the rudder of the Bismarck was critically damaged by a torpedo from an aircraft launched by HMS Ark Royal, the battleship’s fate was sealed.

The damage rendered Bismarck almost unmaneuverable, forcing it to sail in a large circle.

This mechanical impairment drastically reduced its tactical options and ability to escape or effectively position itself for combat, making it an easier target for the British fleet.

By the morning of May 27, the British naval forces had closed in on the crippled Bismarck.

The group was led by the battleships HMS King George V and HMS Rodney, accompanied by cruisers and destroyers including HMS Norfolk, HMS Dorsetshire, and several others.

HMS Rodney and HMS King George V opened the battle with their main batteries at a range of approximately 12 miles.

What followed was one of the most intense bombardments in naval history.

Rodney, armed with sixteen-inch guns, and King George V, with fourteen-inch guns, unleashed a relentless barrage on Bismarck.

The German crew fought back with whatever operational weaponry they had left, but their efforts were largely ineffective given their ship’s compromised maneuverability and the overwhelming firepower they faced.

The British battleships hammered Bismarck with hundreds of heavy-caliber shells and torpedoes over the course of several hours.

The intensity of the bombardment was such that it systematically dismantled Bismarck’s superstructure, disabled its gun turrets, and caused fires to rage across the ship.

The ship’s armor, though formidable, was eventually penetrated by the relentless British fire.

HMS Rodnet fireing her guns at the Bismarck.

HMS Rodnet fireing her guns at the Bismarck.

Observers described the scene as one of utter devastation, with Bismarck enveloped in smoke and fire, listing heavily to port, and gradually losing operational capability.

Despite the desperate situation, the German crew continued to resist until the ship was no longer combat-effective.

As Bismarck’s situation grew increasingly dire, the order was given by the British to launch torpedoes to hasten the end.

HMS Dorsetshire fired several torpedoes, which struck Bismarck, contributing to the final crippling of the ship.

At approximately 10:40 AM, the once mighty Bismarck capsized and sank, disappearing beneath the Atlantic waves.

Out of its crew of over 2,200 men, only 114 survived, being rescued by British and German vessels, the majority by HMS Dorsetshire.